In the years before he turned seventeen, Domeric had grown

up in the harder half of the country. Red marshes and thick groves of

dirt and dead men that had wandered off an eye too far and foot too

deep, like haunted marks that marred the flat plains of swamp, buried

only a stone’s throw from the foot path unbeknownst to the

passerby’s until their bodies came up with the summer rains.

In the years before he turned seventeen, Domeric had grown

up in the harder half of the country. Red marshes and thick groves of

dirt and dead men that had wandered off an eye too far and foot too

deep, like haunted marks that marred the flat plains of swamp, buried

only a stone’s throw from the foot path unbeknownst to the

passerby’s until their bodies came up with the summer rains.

It was hardly uncommon—both within the city walls and out

to the surrounding towns—to hear stories of stableboy’s or

farmhands who’d got swept up by an avalanche of mud and rain,

drowned before the summer’s end and not found til the next summer

season had salted the earth in a title wave of short held grief and pity.

Only to be repeated again before the leaves turned and the rains

contuined to drown the earth in a sorrowful muddy well.

The weather never an eve too bright, either. The air thick

with the swells of black monsoons durning the wet summers and

damp springs and little softer during the winters, only differentiated

with an unbroken chill that seemed to beat to the bone under layers

of furs and hearths and wet-boots. Domeric scarcely imaged

anywhere on the continent might look so different than the cold

eastern tip of Biwreye. Yet, the battlement was miles of country out,

long past the acadiana and the marshlands and, as Ser Dane

Hughes—a tall, stout man, who had been Domeric’s squire knight

during his time in the battlement—had said, they were a three week’s

ride south; with the sky a bleeting blue, like the speckled shell of an

egg. And the summer, as it had been, was already deceptively warm.

It was the most beautiful part of the country, yet, sorrowfully,

Domeric thought, no less full of ghosts and dead men.

They'd been in the distance from a large southern castle for

some time, a looming weave of white stones that sat atop a green

hill. The tall peak of it stuck out from a sea of rolling grass that eemed to wrap for miles.

Portly, in that it appeared so thick and

deep one could feasibly assume they might just about stumble off the

edge of the world if they walked into it. And no less humbly was the

castle itself, stiff against the prodigal sky as the deep spur of the sun

overhead hung like a yellow egg yolk, casting a wide shadow down

from the keep that carved the grass below into a dark pit.

Domeric thought the thing might about swallow him whole,

if he hadn't felt Favel beneath him kicking up bouts of rocks and

earth with his unsteady gait. The image like a picturesque old world

canvas, plastered against the wall of the abbey in his home city as a

sharped edged reminder of what penitence had to offer. The sort of

thing he was sure he'd seen in the pages of some fairytale. Nothing

like the tall stone obelisks that stuck up from the wide landscape

back in Biwreye, dutiful in their watch. This castle, born of beauty

and ambition, was the kind fit for kings, and knights, and maidens

fair and only really real in the intangible depths of dreams.

"Ever been to a castle like that?" Toke, one of the other noble

boys in the cavalry, whispered beside him.

Toke was about a year or so Domeric's senior, with sorry

eyes and a skittish horse named Dancer who had once ridden in

tourneys before Toke had joined the Templar. When he'd first met

Toke, Domeric had asked him how that'd come to be. A tourney

horse to war. As Toke had said, quite listlessly, he'd once been the

page to a tourney knight.

"Never much been to a real castle." Domeric said, Favel's

foot sinking into a deep hole left in the dirt from the boat-carriages

and wagons ahead. "Let alone a castle like that."

Though he'd imagined them plenty fold when he was much

younger. Stories of knights in white armor and ladies in silk dresses

gathered to court in castles that drowned the land around them like

the mast of a black ship.

“Guess that’s what being a high lord gets you.” Toke said,

tying a flask of watered-down wine to Dancer’s side as they trampled

over the freshly kicked earth. “Think you’ll ever live in one, one

day?”

Favel hit another dip in the worn wagon path cut between the

thick walls of rolling grass, wrapping up to the castle’s frame like a

warm bed.

No. Is what he wanted to say. Fantastical and grand that it

was, like an untouchable monument from some long worn and lost

moment in time. And quite stilly, as he stared across the open fields

and hills that towered somewhere between the far plains of land west

and the tawny coast, he found himself having a hard time imagining

anyone having lived there at all.

“I’ve always wanted to live somewhere warmer.” Is what he

said, instead. “I’d imagine this would be good a place as any to

start.”

And it was, good as any. The walls of the castle drawn closer

as they rode further up the hillside. And perhaps he might never live

in a place such as this, but as he watched the sun dip down lower on

the horizon, he understood plain as any why. Because people were

not meant to live in dreams. And so horribly, the fair and framed face

of the castle itself was as much a disincarnated dream as any place

possibly could be, and too, inexplicably with the realization,

Domeric felt a sense of dread looming underneath the wide, empty

sky. Summer birds with white wings beating over in a one two time,

loud as all terror.

The sky was a deep, angry orange by the time they'd arrived

at the castle. The bleached bricks that toppled either side of the front

gates tinged peach like the warm hearth of a fire as the sun burned its

reflection to the lime-washed walls and bronze carvings that

languished in tangled mass on the front gates' thick iron bars. The

flushed noses of carefully patinated men and women drawn cold as

the heavy doors brushed open and small lines of horses and wagons

catered by in droves.

It was not quite evening, far enough from that there was little

rest and much fanfare from the excitement the towered legs of castle

spires inspired in boys who'd never been a wagon ride away from

their homes. And among them, too, Domeric felt sickly awestruck by

the unfathomable sight of the white stones and hickory trees dusted

in shades of jeweled greens and golds. Not nearly done in justice by

the small, lithe body of it that had been dotted in the distance of the

horizon.

And though sick with exhaustion, he'd not much in the way

of rest before taking to the tasks of unsaddling horses, alongside a

few of the other boys, including Toke and an irritating boy named

Bello.

Bello was the same age as Domeric, with a thin nose that had

been broken crooked and a mad grin that probably pleased no one

but Bello himself, since it only ever followed the spit of a flagged

taunt. And at some point, Domeric figured Bello must have mistaken

them as friends because he'd one evening, during their encampment

at a town outside Longleat, come to Domeric's post with his teeth

pressed wide to his ears and more tittering than Domeric took an

interest in.

"Good news, m' on your post." Bello had said.

Domeric hadn't seen how that was good news, but he'd also

made no effort to protest, and had since been suffering through the

whistle-toned blow of Bello's voice as he filled the empty air of the

castle's stables with the chatter of how he'd spent the previous

evening outside of Rhys with a homely woman named Jovena.

According to Bello, she was a well built brunette who

frequented the local alehouse, though Domeric had his suspects that

she didn’t spend her evenings waiting there for folks like Bello to

sweep her off her feet in romantic tizzy.

According to Bello, she was a well built brunette who

frequented the local alehouse, though Domeric had his suspects that

she didn’t spend her evenings waiting there for folks like Bello to

sweep her off her feet in romantic tizzy.

Bello then had spent the rest of the evening attempting to

convince both Domeric and Toke that it might be fun to go down

again that same night after their dinners—a sorry little thing of

creamed fish and pitiful wine that they'd pulled with them in their

wagons—as Bello apparently had a friend who'd grown up nearby

and knew his way in and out like a weasel. To which Domeric made

a show of a stomach upset and an array of other excuses that might

get himself out such a dreadful task, and Toke, avoidant as he was,

had simply disappeared wordlessly at some inconspicuous point

during their meal. So sly Domeric hadn't even noticed his absence

until he'd turned to get Toke's opinion on the matter, only to find the

seat beside him empty as the open sea.

It wasn't until later in the evening that he'd taken the

opportunity to slip down to the castle's oratory. Domeric had never

considered himself overly virtuous, nor ripe with piety. Moreso, he

held with his visits a deep sense of duty best off carried by every

man, knight or otherwise—though ostensibly the prospects of

knighthood softened the labor of the task greatly. Being well what it

was. A riotous awning of the prestigious and exemplary, rather than

simply being born of petty honor and bedded flowers that wilted and

died with rains, and droughts, and fair weather. And as he walked

through the echoed halls of the carved chapel, he couldn't help but

believe there ought to be the watchful eyes of God, here, too.

Horribly observed by the empty room.

All tall pillars and saddled gold, lit by candles that cast large

shadows against the tiled floors and paled beneath the slipped reds

that drove down from the glass ceiling in an illuminating display of

ornery moonlight. Only aided in the strange, empty nature by the

bright stained oil paintings that sat stone in a leafed display around

the edges of the room. Great big faces of men and women who were

important enough that their likeness had been written down in a

desperate attempt at remembrance against the race of time. Like

fighting an invisible stranger who cared little at all for the fight, or

even a winner for that matter. Though perhaps that was what made

the defiance all so futile to begin.

He’d been to the abbey in Biwreye often. Smaller than the

one in Somset, with less grandeur. The stones worn and the candles

held by small iron scones, and the only painting being that of a

black-varnished oil depicting a legie knight that hung staunchly on

the back wall. He was an important knight. The kind talked of in

books and the founder of the Knight’s Templar. And Domeric would

look up at the painting often. The bone-bleached armor of the man as

he sat atop the back of an obsidian horse, like a holy knight of myth.

Domeric frequently imagined himself as the man in the painting, as

any young boy might. God, gold, and glory pressed on the skin of an

honorable man, as idyllic and untouched as the Gods themselves.

Human, but surely not anything close to mortal; at least, that was

what Domeric had thought as far as the man in the painting went.

And no less indefinite did the lords and ladies in the Somset

oratory look. Fine men in red capes and preened expressions

postured in an immortal sense of valor despite their existence as a

temporary fixture of the castle in a long set of lineage.

Stuck out among them was a painting of a pale-faced

woman. The tilt of her lips like the ruby flat leaves of a plum tree,

though her features saddled the canvas like ruined stone, carved in a

ladden expression that followed him morose through the chapel’s

stalls as he stepped towards the perched altar sat center stage.

Might she have been either a lady or daughter at some point

in the castle’s history? He did not know, but there was a grave

sadness to the painting he had been unable to shake for the weeks following, and the stone halls of the castle, despite having been

basking in the pleasant heat of the summer evening air, had been

plagued by an autumnal chill not unlike a vague sickness that seemed

to persist no matter the weather.

Too, by the wake of the morning, it was with little surprise

he'd slept poorly as the weeks turned, on account of the deep

humidity and a black pit of dreams. Like a stranger intent to drown

him in a sea of steel. The image of a boy with an arrow through the

helm of his eye and a neck bent into the dirt as a wash of horses and

clotted boots sullied through red mud. Although he hadn't gotten

much a good night of sleep since long before that evening too. The

dreams of ghosts and a cold white eye pierced by copper steel

hanging like an executioner's blade since the night he'd shot the

arrow. And he wondered if Ser Dane suffered such bouts of

sleeplessness and harrowing dreams as well, or perhaps the haunting

feeling was something he'd long gotten used to as the price of a battle

won and the grace of God to wake the next morning after. And he

liked to imagine a far-off evening in a bed of fine linen and silks in a

warm castle, in a warm city where such a thing might not bother him

at all. The penance of noble endeavors steeped with deep rewards

rather than merciless guilt.

Though, he was saved thankfully by the carrying voices of

the infantry and cavalry outside bellowing in through the small

stone-cut window of his room, lined with various colors of stained

glass that danced peacefully onto the aching cracks of the stone

floors. He hadn't recalled much of his southern history, and he had

little clue who had owned the castle before the Knights of Templar

had, but he'd imagined they must have been very wealthy.

It was still nearly dark by the time he'd made his way from

his room to the stable where he and Toke had been intended to water

the horses for the morning before breakfast.

Llewellyn, one of the younger squires, had been amongst

them as well. Far more eager than either Domeric or Toke had been

at such an early hour, and he'd spent most of the cool, silvery

morning chirping in a brimmed dawning excitement, new to the

prospects of travel at such an early age.

"I've never had a room so big." Llewellyn said as he tossed a

cold wash over a horse named Bayard, running him down with a

fine-toothed curry comb. "I've got a room my own of course, but

never one so wide. Be hesitant to call anything a castle with one's

like this."

"Decadent is what I call it," Toke said, "don't think anyone

needs so much stuff, you ask me, castle's in better hands now."

Toke, though plenty wealthy, had grown up further north,

where winters started by mid-autumn and didn't wane until the end of

spring. Castle's often threadbare, likely more than even Domeric was

used to by nature of bad weather, and built to withstand utility over

all else. And it wasn't much hard for Domeric to believe that was

where Toke got his general disposition, too. Though he imagined it

might be an unpleasant way to live such as that, being so un-privy to

all of life's thoughtful futilities.

"Who'd did own the place anyway," Domeric asked. Toke's

brow raised to him as he razored a knot from the side of Dancer's

mane. "Never much been good with my southern lords n' dukes."

"The Godfrey's," Toke said with a pause, "well, was

the Godfrey's last I think. The portraits go as far back to Lord

Norwitch, though, who'd had the place before."

"They teach much history where you're from?" Llewellyn

asked, his own horse Morel rather skittish and easy to spook. A

match made since Llewellyn himself was, well and things considered, a shy boy. His voice small and drowned like the scurry of

a cellar mouse as he talked towards the tops of his feet. "Never much

good at history in my lessons; I'm a better archer."

A hard image, the thought of Llewellyn killing anything

besides strawmen with wooden swords and weaved targets. Though

that was really all the fun of it, anyways.

"You'd seen the portraits?" Domeric asked, and he couldn't

quite picture Toke stood at the foot of a chapel bench reciting words

of prayer, though it might have been a funny image if he did.

"No." Toke said, grabbing a bridle off a woodcut saddle rack

and hanging it over Dancer's tipped nose. "But I know of them.

Probably more oils here than elsewhere, least from what I

remember."

"And why so?"

"Rich family, big keep, big heads," Toke answered, barely a

beat missed as he chewed through his stream of thought. "Lots of

history in a place like this. Lot's a rumor, too." Toke adjusted the

hang of the bridle with a rough pull, giving the tanned leather a loud

smack as it sat straight on the dent of Dancer’s back. "That's what

happens when people have the time to sit on their asses all day, I say.

They come up with stuff to worry about."

Though the statement just made Toke sound like a rather big

cynic.

“Well don’t just be sorry about it,” Domeric said, “what’s the

rumor?”

“It’s a dumb rumor.” Toke pursed his lips to a line, “And I’m

not sorry about it. It’s a ghost tale, mostly. They say the keep is

haunted.”

“Doesn’t look like any haunted keep I’ve ever seen.”

“That’s because it’s not haunted.” Toke made a point of

emphasis as he tossed his manner of tools back to their bucket.

"People say it's haunted, doesn't mean it's haunted."

"And why not?" This time, it was Llewellyn, who spoke,

eyes wide as a field deer as Toke squinted his eyes at him.

"You ever seen a ghost?" Toke gave a quick ring of his wet

cloth before setting it off to dry over the stables side, gaze fixed

down on Llewellyn, not waiting for him to answer his tall-taled

rhetorical. "No, cause ghosts aren't real."

"My mother said our keep was haunted." Llewellyn offered.

Which only caused Toke to laugh.

"My mother used to tell me there were Blemmyes cross the

sea'," he gave a mild shrug, "not everything's the way people say it

is."

Though people often say things for a reason.

"What's the place haunted for, anyway?" Domeric

interjected. It was a curious kind of place the be haunted, Magnolia

tree’s and bright windows that carried that carried light like the soft

break of dawn.

"One of the ladies," Toke pointed to a tower on the castles

east side, a tall spire above the chapel and great hall’s end, "killed

herself in that tower. After a battle, say her lover was killed. Some

knight or other. Bad reason to kill yourself if you ask me."

Although Domeric thought it made for a rather lousy ghost

story, seeing that it was mostly just sad. A terrible kind of tragedy.

But he didn’t much forget Toke’s words either. And in the weeks

following, he’d been curious enough to, at the very least, track down

the woman’s name. Eilema Godfrey. Same as the painted woman in

the Somset oratory. Coppery hair and sharp eyes over a thin, sloped

nose that drew down to the flat of her lips. She was quite pretty,

though not in such a standard way. And when she looked down at

him with her tragically morose expression, he couldn’t help but

wonder what her life must’ve been like.

For the most part, in the week to follow, Domeric had spent

most of his time at the small wooden desk shoved in the far corner of

his room. Several shelves worth of books piled around in small

puddles as he made work of reading through the leafed pages.

He'd found, quite unfortunately, there was very little to do outside a

litany of chores and base responsibilities, besides perhaps drink and

sew havoc on the small town of Ydolastre that was a half-hour ride

away, which hadn't been allowed, but many of the boys did anyway.

For the most part, in the week to follow, Domeric had spent

most of his time at the small wooden desk shoved in the far corner of

his room. Several shelves worth of books piled around in small

puddles as he made work of reading through the leafed pages.

He'd found, quite unfortunately, there was very little to do outside a

litany of chores and base responsibilities, besides perhaps drink and

sew havoc on the small town of Ydolastre that was a half-hour ride

away, which hadn't been allowed, but many of the boys did anyway.

Bello, on occasion, got out to do so as well, with a group of

other men in the calvary and his mousy little gossip friend Wyket.

And he had tried many times to convince Domeric that it might be

fun outside of all the sorry excuses and flat rejections. Which mostly

resulted in Wyket coming up with a number of increasingly absurd

reasons why Domeric didn't want to come, likely ranging from the

fact he simply had nothing better to do.

Rather instead, Domeric had spent most of the evening in his

room with a stack of books he had found in the castle's study, a large,

tall, cavernous chamber that went on for rows and rows and seemed

like it may never end in a senseless sort of gaudy collection. And he

doubted most the books had been read at any point throught their

existence in the castle walls based on the thin line of dust that had

crept over the page tops and built stucco shelves that protruded from

the library walls.

He'd chalked his bitter curiosity up to the sheer boredom he'd

been offered by the never-waning end of days and night's that he'd

spent in Somset. Too, like a hanging ghost, the impressioned face of

the woman in the painting compelling his interest around historical

subject matters in a strange, unshakeable hum, that he seemed to

worry around his thoughts endlessly. And despite being renowned for

dying, the pale bound books had surprisingly little to offer in the way

of the history of the woman. A stranger in her own life. He read

down a list of names in a large bible book that documented family

histories.

Mynde Godfrey—1216 - 1244

Married to Ysabel of Reweth

Meiler Godfrey— 1237 - 1260

Married to Lyana of Ashdow

He flipped through several of the pages. The room a depressing cool

as the night air swept through the cracks starting in the castle's walls.

Errc Godfrey— 1322 - 1358

Married to Ysoria of Apelles

Children, Errc Godfrey the younger, Aymeric Godfrey,

Eilema Godfrey.

It wasn't until the fourth or fifth book that he'd found

something more than the woman's year of birth and the name of her

father and brothers. It was a small biography, of only a few words.

Eilema Godfrey— 1339 - 1357

Eilema was born to Ysoria of Apelles and Errc

Godfrey in the city of Somset. She resided in Somset until her death

in 1357, where she took her own life after the castle was captured by

invading forces. She died with no children and was never married.

Despite the petty rumors of her ghost, it was as though the

histories had eaten her alive. A sad sort of destiny to end up with.

He wondered what his own page might look like. Domeric

Kane— 1402, born to Jane of Wakefield and Yorric Kane in Biwreye.

He hoped there might be more than that. Thirteen words on a page.

And most terribly, he thought again of the boy from his nightmares.

The one he had killed. Might he have a page at all? Or even so much

a name in a book somewhere? Likely not. And when Domeric finally

went to sleep that evening, he saw a woman with red hair and a

perfect arrow in his dreams.

The next of the weeks at the castle passed slow. A tirade

wakefulness and restless sleep that he'd attributed to the development

of his sudden break into madness, or what he assumed must be based

on all accounts.

He'd start his mornings in the stables and spend his days a

stone's throw from Ser Dane until the evenings, in which he mostly

had to himself. Although he'd found the longer he stayed in the

castle, the further the evenings stretched. Thoughts of the portrait and

the woman hanging over him like a blank shadow.

Like Toke, he'd little believed in ghosts. Tall stories mothers

tell their children or children tell each other to estrange and terrify.

But as the days passed, he had started to notice that the image of the

woman persisted like a blazing chill. And Domeric would often

swear he'd seen her face or heard a woman's voice echo behind him

down a long castle hall. A figure in a dovecote or buried in the faces

of the great hall, only to find the castle empty and devoid of any

woman to speak. It was maddening. And were Domeric any younger,

he might have attributed to a divine sign or an omen, but now

Domeric had simply begun to wonder if the boredom had caused him

to lose his mind.

The worst instance had been the evening he'd finally agreed

to go with Bello down to the small traveler's town of Ydolastre

between Somset and Rys.

Bello had been beside himself giddy, with the effect that his

persistence had finally worn down what little patience Domeric had,

only to simply disappear the moment they'd gotten themselves seated

in some partly derelict alehouse, leaving Domeric alone with Wyket,

who'd already begun to drink himself a face closer to death, and

another boy a bit older than all them, who was also from the east.

The boy, Orvyn, had joined the calvary around the same time

Domeric had, meaning he'd been at Ashdow, unlike many of the

others who'd joined a few weeks later and had yet to see an eye of

battle. And they'd had a not terribly unpleasant conversation about

where in the east the boy was from, his family, and how he'd ended

up with the Knights Templar.

"Most I saw it, just good for being away from home. Not

terrible people, my family really, but I've got three elder

brothers—not much else one can do but be a knight."

Domeric wanted to say that he couldn't have related less.

Being the eldest of three, but instead, he attempted to offer what he'd

hoped came across as an understanding look, though there was little

guarantee that it had.

"What about you, why a knight?" Orvyn asked, a round wine

cup pressed to his palm as he leaned back from the table, the orange

glow from a nearby lantern casting a deep shadow that cut across the

hollow curve of his cheek.

"I've just always wanted to be, I suppose." And when he said

it, he realized just how foolish that sounded, a warm rush of blood

washing over him as Orvyn laughed. Though with no intent ot

malice, met by the embarrassment of it all the same. He'd reached to

say something more when the room was cut by a loud crash of wood

hitting dull against the floor, and Wyket's body way splayed against

it, hisstinh the ground with a rather painful-sounding thud, the back

back of his chair toppled over flat bedside him.

He'd drunk himself straight from the seat of his chair, and

Domeric and Orvyn did nothing but stare at the sorry scene for a

moment longer than they probably should have all sense of

reasonable worry disappeared in the place of shock.

"Someone should probably take him back." Orvyn said with

a nod, broad-faced and nettled. "You remember the back way, in and

out?" Oryvn asked, and Domeric nodded. "I'll go find Bello, probably off somewhere, damn fool he is. Go ahead and take him

back will you."

Domeric hadn't much been looking forward to the task, and

though Wkyet wasn't large for his age, neither was he reasonably

light.

They'd been halfway up to the back end of the castle when

Domeric caught the sound of voices carried in the distance.

Taking a moment's care to duck into the small set of birch

trees that scattered in a light covering around the castle’s edges.

Having little interest in taking whatever consequence came with

being caught outside the castle walls unprompted. As the voices

grew, the silhouette of several men on horses became apparent under

the white cast of the moon. And he'd nearly dropped Wyket face

down in the dirt. The face of the lady in the portrait floating by on

the back of a black horse like an omen of death.

He'd made good to take Wyket back through the back end

gates in a hurry and had simply dumped him in a bale of hay by the

time they'd made it back to the castle walls. Scurrying off to his own

room though guilty of some terrible crime, which in a sense he may

have been. Though mostly, he couldn't shake the hallow of broken

paranoia that had followed him. That perhaps the castle, or all of

Somset, might be haunted—or simply, and even worse, he'd well and

certainly lost it.

That evening, he dreamed he drowned in a sea of grass, and he'd

awoken to the cold light of the morning sun as it barely ran thin over

the crossed glass of his chamber's window.

That evening, he dreamed he drowned in a sea of grass, and he'd

awoken to the cold light of the morning sun as it barely ran thin over

the crossed glass of his chamber's window.

He'd gone down to stables barely dressed, eyes still bleak

and jaw still tense from the grip of his dreams and the evening

before. Though when he'd made it to the rough-cut horse shed, Bello,

chipper as all hell despite being out and gone for most the evening,

was near shouting at poor Llewellyn, who stood sheepishly behind

Morel as though it would stop the onslaught of Bello's voice.

"One of the ladies at the tavern told me." He could tell Morel

was starting to spook from the commotion, ears tilted like a

wind-sewn flag and back leg kicked hard into the dirt. "Saw em'

riding this way last night."

"Saw who riding?"

He saw Bello jump in a quick turn, seeming almost

embarrassed for a moment by the quick interruption before falling

back to his typical, blustering, grin.

"Ser Godwin." His teeth almost split open on the words.

"He's headed up to the castle." It was only then, that Domeric

understood Bello's splitting excitement. "Heard too they had a

prisoner with them."

"To the castle?" Domeric asked. The men from the previous

night came to him in pieces. The cast of a black horse wide on the

grassy landscape.

"Closest place between Certes and Apelles."

"Why Certes?"

"Well, I dunno know. That's what Orvyn said, he knows all

about these sorts of things. Certes and Apelles. Must be someone

important to go all the way to the queen's city."

Dinner was loud that evening. The hall, a buzz with

excitement.

Word had gotten around of Ser Godwin's arrival. With

Domeric having overheard some boys, Wyket and a fellow he didn't

know quite as well, out near the Dovecoat saying they'd seen him

ride through the gates that same morning. And Bello had been on

again about some something or other— likely a listless tirade about

the Jovena woman Bello always insisted upon—when his mouth bit

closed like a vicious snapper. Whipped by some mysterious sense. At

first, Domeric was grateful, thinking maybe he'd become suddenly

aware of how irritating he was, until he realized the entire hall had

fallen silent, eyes turned to the helm of the room where a man in

white armor had seated himself firm at the head of a table, next to

Ser Dane and the other ordained knights. And it was the first time

Domeric had seen the man in person. Ser Godwin, founder of the

knights Templar.

He was older than the painting Domeric had seen. His hair

feathering white around the edges of his temples, and his face fuller

with the skin of age and years well lived, though no less imposing,

almost half a foot taller than Ser Dane, his amor white as bone and

ivory.

“Well don’t silence yourself on my behalf.” Ser Godwin

spoke, face raised in a brazen grin as he gave the room a dismissive

wave. “Drink! It’s a night to celebrate,” he thrust his glass into the

air, a red spill blossoming over the cup's lip. “The War’s just about

over.”

And despite the great excitement, Domeric couldn't help but

feel an air of ill ease, and the advent of Bello's yelps and shouts at

people sitting three seats down the table did little to help. He’d

slipped off with little less than a word before the dinners end.

It was in his early leave that he ended up wandering down a

large hall in one of the castle's wings. Comprised of deft pillars and

laid out like an expansive labyrinth from an old, worn-out myth, in

which a beast waits somewhere in the belly below. Devil wings and a

goat's head, or some other terrible amalgamation of beast and man to

roam. And he'd somewhere along the way managed into an area of

near darkness. The streams of moonlight suddenly cut, and Domeric,

unsure of at what point they'd disappeared.

The stones of the room were less kept, too, like black coal

lit by a few dim candles that had been placed on iron holds along the

wall, casting large obtrusive shadows before mostly disappearing

completely like something from a bad ghost story. Which Domeric

was always sorely reminded of when alone in the castle at night.

He placed one hand along the wall, attempting to feel his

way to an exit; when he turned around a corner, the pale face of a

woman stuck out to him in the darkness.

It was in this moment of paranoid weakness that his heart

nearly hit his throat, and he'd barely choked down his startled yell

before he'd realized the figure wasn't spectral of any sort. Rather that

of a girl.

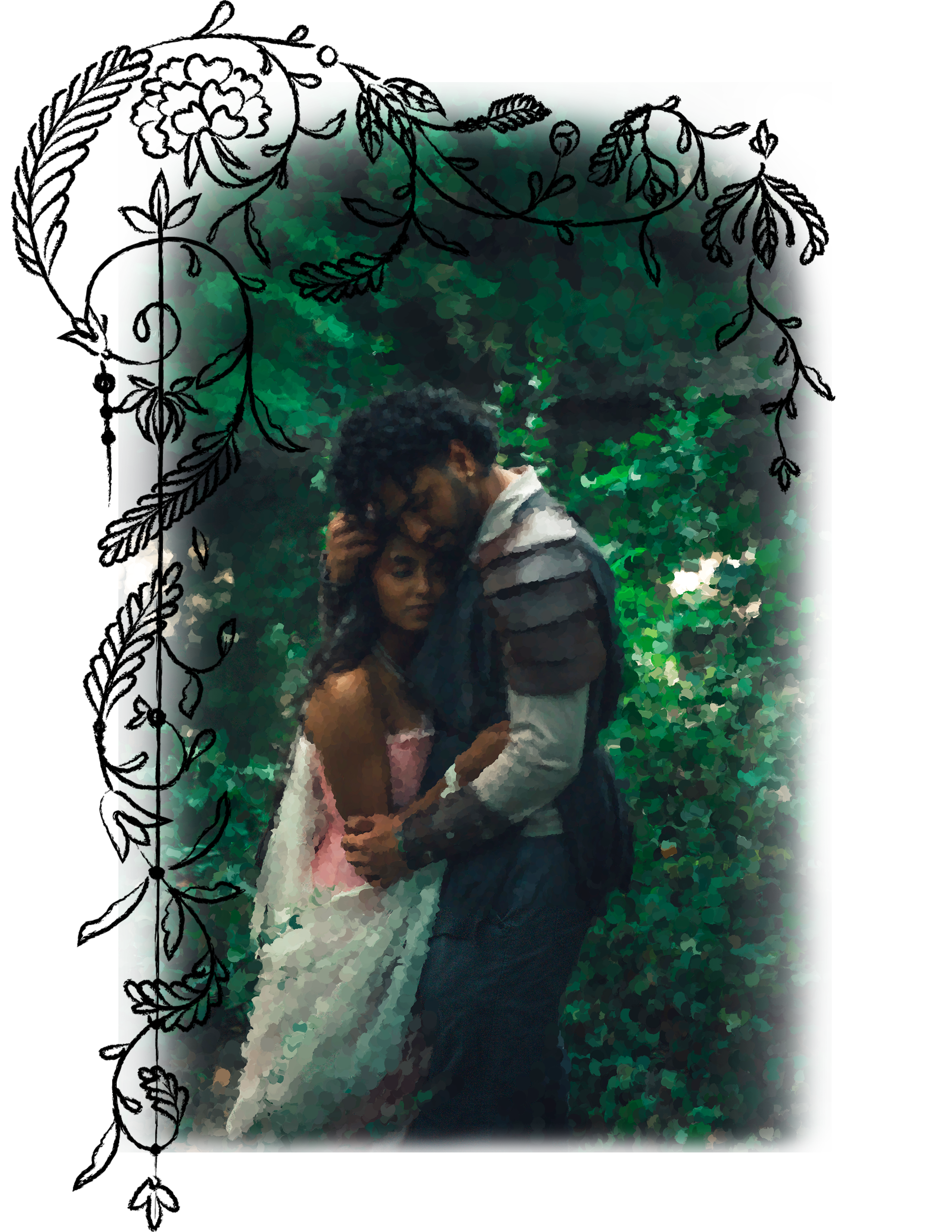

A small girl, famished looking, like the black corvids that

hummed overhead in Biwreye, with rusted hair that hung in loose,

thin waves, weighed down by the weight of itself and splayed over

the blushed pink of her dress, the fabric pale, like it had been

bleached in the sun over the course of several days. And she had a

fine purple bruise over the bust of her cheek.

She looked nearly surprised as Domeric himself had been,

her eyes wide and lips slightly pulled apart before her brows knit

together in a sort of recognition. Of what, he was unsure.

"I can't be that terrible to look at." The girl said, and

suddenly, Domeric felt rather embarrassed.

"I thought you were a ghost," Domeric offered, not as willed

with the declaration as he'd have liked to been. And the girl raised

her brows with a burrowed frown.

"A ghost? And do you always believe in such nonsense?"

The girl was stood less than a foot from the wall. A ring of fine

chains drawn heavy around her wrists. And Domeric was met with the passive recognition that this might've been the girl on the horse,

the one Bello had said Ser Godwin was taking to Certes.

"Lots of people say their keeps are haunted."

"Lots of people are fools, then." The girl said plainly.

"There's no such thing as ghosts."

Though she may have well been one. With her long, thin

nose and perched lips. The cotton face of the dead woman that had

been haunting his dreams.

"Says who?" Domeric said. "Can't be that everyone's a liar."

"May well that they can be." She sat down against the wall,

the fabric of her dress pooling like a small pond by her feet. "And

what're you, anyway?" She asked, not impolite but not terribly

friendly either, and the question caught Domeric off guard.

"I'm knight," Domeric responded, a bit dithered. The girl

contuining to worry faintly the hem of her dress.

"You look too young to be a knight, and that's not what I

meant, anyway. What's it you're down here for?"

It was then that Domeric realized the perhaps bizarre nature

of his appearance; just as off-guard as he might have been by the

girl's sudden appearance, so too to her, strange did he probably seem.

Wandering around the dark in imposing stature with seeming little

reason as to why.

"I got lost." Domeric offered, and she seemed to accept his

answer unquestionably.

"All southern castles are quite confusing, I think. No rhyme

or reason, really; all the quarters built with separate visions in mind.

The castle in Apelles isn't much different. Really, what need is there

for so many different passageways?"

"Escapes, maybe," Domeric said, without putting much

thought into it, though he quickly realized how crass it might seem

on account of the girl's situation. "Or perhaps, confuse, I mean, any

strangers that might find their way in."

"Perhaps so," the girl said, "though I've never seen strangers

break their way into a castle. You're with Ser Godwin?"

"Ser Dane," Domeric corrected. On account of the fact he'd

never much met Ser Godwin, not personally.

"If you're with the Templar," the girl enunciated, "you're with

Ser Godwin."

"Then yes, I suppose that makes me with Ser Godwin."

"I don't understand why, he's not all very nice, you know."

Domeric had never assumed he might be. In fact, he never

assumed anything about Ser Godwin at all outside of the things he

already knew. Which was that he founded the Templar and was an

exemplary knight.

"He has a cause to support," Domeric said, and though he

might've felt bad for the girl, grace in such circumstance was a

luxury.

"I've not done anything, you know." The girl said this time

from the blue, no longer looking down at her hands, but instead, her

eye's wide to Domeric. "Really I haven't. The cause must be terrible

so to cause all this. He killed my brother, too, down in Apelles. We

hadn't done a thing."

"Your brother started a war."

"My uncle started a war." The girl corrected. "My brother

died for nothing."

"Maybe so, but it's still war."

"And you'd die for this cause?"

"I think if I were to die," Domeric paused, "it would be best

to die for something I believe in."

"And is this what you believe in?"

What Domeric believed in—

"Ser Godwin and the chruch have done good by my family.

I'd be a fool not to believe in them."

"Be a fool, then.”

He'd spent most of the next two days in a sour mood. Toke

had asked him at breakfast what happened, but Bello just made to dig

and make his mood worse. Needless jabs as they huddled around the

training yard like he was making some sport of the irritation.

"You're a shit archer," Bello said as Domeric notched another

arrow, the last one dug into the fence post behind the archery stands

mockingly.

"I'm a shit archer 'cause you keep talking," though truly, he

hadn't shot a straight arrow in weeks. When with every time he tried,

the face of the boy hung fatalisticly with an empty spot where his eye

should be. He watched the arrow sail off and into a patch of dirt a

row from the target's front.

"Nah," Bello said, giving him a pat on the shoulder, "looks

like you're a shit archer 'cause you're a shit archer."

Though despite his talk, Bello himself wasn't a much better

archer. Every arrow missed terribly to the dirt. The sight making

Domeric smile just a tad.

After dinner that next evening, one of the boys had stopped

him as he left the hall. Bello's friend Wyket. He'd nodded towards the

long table where Ser Dane and some of the other knights often sat.

"Hugues wants to see you," Wyket said. And Domeric could

feel the subtle itch of paranoia return. Worried that perhaps he had

heard about their excursion to Ydolastre or some other of his

wandering offenses. Wyket's drawn, dour expression doing little to

edge his nerves.

"What for?" Domeric asked, and Wyket just shrugged

solemnly.

"Dunno. Told me to go get you, though."

Domeric had wanted to argue, but instead, he stood, taking a

quick turn to the foot of the long table.

"You wanted to see me?" he said, Ser Dane's head turning in

a long arc to face Domeric. He seemed a tad drunk.

"Domeric!" Hugues said, girn wide as he waved Domeric

forward. "You look glum? I don't suppose Wyket scared you. Has a

way of delivering news like the dead, that one."

To that, Domeric might agree.

"Sit down, drink with me." Ser Dane raised his glass. "You're

a good squire, you know, grown into a good man. You'd be an even

better knight."

And despite the outward sense of cheer, he seemed morose,

for a reason Domeric couldn't pinpoint.

"You ever met Cenric?" Ser Dane said suddenly. "He's a

good knight, too. Maybe even the best of 'em." He took a drink from

his glass. "He's lookin for a squire. Lost his on the field down in

Apelles when they took the city."

He'd made his way to the room where Ser Dane had said to

go not long after. It was a dim chamber in the upper east wing of the

castle, with white walls that cast dark grey under the flickering light

of the oil lamp set on the desk where Ser Godwin was sat hunched

over a piece of white parchment, the metal tip of his ink pen

scratching along the ridged paper.

"Domeric, come in." Ser Godwin said, his gaze not lifted

from his parchment even though he'd been the one to request

Domeric. "Ser Dane and I, we go quite back in the years. Good deal

of it, it was. Met before the Templar even existed, down in Albury.

He likes to act all humble, really, that one, but he's got more skill

than spirit I like to think."

It was something Domeric hadn't known. Ser Dane being a

mostly private man. With Domeric only ever hearing rare bits of it on

occasion, about his time in Certe's or across the sea in Soveryen. And

in the dim light, hunched over his desk, Domeric thought Ser

Godwin looked little like the knight in the painting he'd seen hung

the Biwreye abbey. Older and more estranged as he was illuminated

by the candlelight. Abhorrently human.

"I'll get to the point of it." Ser Godwin said abruptly, tapping

the stiff body of his pen around the glass interior of its inkbottle. "Ser

Dane spoke quite highly of you. And I'm out a squire. I'd like for you

to work under me until I take leave from the castle."

He lifted his head from the table, staring intently towards

Domeric. And he knew appropriately he should be thanking the man

profusely. Certainly, it was beyond the recognition he would have

ever dreamed. Nor might anyone, dream. But he couldn't escape the

hollow pit that had been sinking in his stomach. Pressing and

drowning his excitement like a thick wall of peat moss hovered over

an impounding log.

“I’m really not all that adept at it.”Domeric said, in the only

response he could muster. And Ser Godwin laughed humorlessly

"See you get your humility from Dane, too. Look at ya." He

waved dismissive, dipping his pen rapidly in its ink pot before

pulling it out in a small wave. "It's just basic duties, mostly. Gaurd,

stables."

"Gaurd?" Domeric asked.

"Mostly just standing nonsense, down in the cellars, though

not much fun. But I trust you're plenty capable."

Domeric wondered if it was the same cellars from the other

day, the dark, ugly walls still fresh in his mind.

"You've got the rest of the night, but you start tomorrow.

Enjoy it, you're almost a knight."

And in a deep irony, he’d slept dreamlessly that night.

In the day following, Wyket, gossip that he was, had told

nearly anyone in the calvary that would hear about Ser Dane calling

him the dinner before. And judged by the expression on Wyket's face

when he caught glimpse of Domeric walking up on him and Bello in

the training yard that afternoon, it was like he'd seen a ghost.

In the day following, Wyket, gossip that he was, had told

nearly anyone in the calvary that would hear about Ser Dane calling

him the dinner before. And judged by the expression on Wyket's face

when he caught glimpse of Domeric walking up on him and Bello in

the training yard that afternoon, it was like he'd seen a ghost.

"Dom—" Wyket started before Bello cut him off.

"Didn't much expect to see you this fine day, thought Ser

Hughues was set to cut your head up or something. That's what

Wyket here said, least."

"For the crime of what?"

"Ydolastre? Being a shitty archer? Dunno, I don't ask those

kinds of questions."

"Well, what was it then?" Wyket said, edged like a guilty

accomplice and probably for a good reason.

"Ser Godwin needs a new squire," Domeric said plainly, and

he was caught off guard by the echo of silence in the training yard as

Bello just stared at him, mouth slightly agape.

"He wants you to squire for him?" Bello said hushed, his

breath barely breaching the base of his lips.

"Suppose so."

"You suppose?" And as he spoke, Bello sounded rather

winded.

The rest of the day had been full of accosting questions, from

Bello and a few others. No better through dinner, either. And

Domeric, though irritable, would have been irate by it if he weren’t

so worried. The thought of the cellar looming over him like a black

cloud through most of the day. No lessened in the evening before he

was to be on his post.

"It's you, then. The not quite a knight from before—" the

girl, who he'd learned from Toke was apparently the queen's cousin,

Elisanna Seymour, began as soon as Domeric had stepped out around

the corner into the muted cast of the room where she sat in plain

view, her appearance little changed outside the fact her bruised cheek

had faded somewhat over the past couple days.

"Knight would've been fine." Domeric said, and Elisanna

smiled dimly into her cheek.

"Well, you aren't a knight." She said, pleased by it. "And I

don't think you ever told me your name, or for that matter asked

mine. Did you know that's common manner's?"

She was quite chatty, and Domeric wondered if she was

bored, too.

"Domeric." Domeric said, though the answer didn't satisfy

her.

"Domeric—?" She drew out.

"Domeric Kane."

"You're from up east then. Biwreye."

It was little often people not from the surrounding towns

ever identified him by name.

"You know Biwreye? "Domeric asked, and Elisanna sat

upright, back pressed against the greying stones of the castle cellar.

"Sure. I know lots of places." She said. "And you never still

did ask my name."

Though Domeric didn't see much reason to.

"I already know your name." He said, and Elisanna seemed

surprised, brows raised and eyes wide with a wild gleam.

"Really?" She asked, and Domeric cleared his throat.

"Elisanna Seymour, the queens cousin from Apelles."

Elisanna slouched back down, feet pointed inwards in a

skewed triangle.

"Seems you do know, then, though bad manner's not to ask

me myself, still."

"And you care lots for these manners?" Domeric asked, and

Elisanna smiled in reply.

"Course." She said. "We've got lots of manners down in

Apelles, and plum trees, and clear rivers. I've never been to Biwreye,

what's it like?"

"It's very wet," Domeric said, and Elisanna seemed

disappointed to be met with such a pale description.

"Well that's not very exciting."

"It's not a very exciting place."

"Tell me about something else, then."

And they'd talked like that for some time til' late evening.

Home cities and Saint's Day's. Surprisingly pleasant despite

Domeric's reservations. And just about as bored as Elisanna seemed,

Domeric had for many weeks, been dragged down by the pressing

spires of Somset and the mid-summer weather, grown hot as kindling

as the summer passed with little else to saddle the time in between.

The white birds singing overhead as the summer reached its peak,

loud as all terror.

The summer had burned down into its hot middle season. The kind

that commonly spelled for rain and monsoons rather than an

oppressive heat that drenched through loose layers of clothing and

arid stone walls, the days of fairer weather past and the season at the

worst of it.

Bello had gotten himself into trouble on several occasions

for slacking off and his frequent visits to Ydolastre, which had been caught out the week before. Complaining of his reprimanding nearly

daily. Either because he'd been bored to death with little elsewhere to

go or brought to protest for being called on his bad behavior; either

way, it had been everyone's problem since, and he doubted there was

anyone in the castle who hadn't heard his list full of complaints.

Domeric had even, on one occasion, so sick of hearing it, relayed as

such to Elisanna, Bello's fry voice echoing.

"And too, ya know, it's not just me. Wyket as much as

anybody, yet not one thing about him. You know what I think, it's

some sort of damn conspiracy."

"Don't think idiocy is a conspiracy, Bello," Toke said as he

threw a tall saddle with an archer's slot over Morel's back. "You

knew it was coming."

"Wasn't coming. Like I said, it's a damn conspiracy."

Although Bello didn't seem to much question why he'd be

the target of such a plot. Likely because if he examined it further,

he'd find far too many holes for it to be a sturdy scapegoat. And

outside his restless complaints, Bello, along with most the other

boys, hadn't left the castle since.

Mostly, too, he'd begun to look forward to his evenings. His

guard duty less a dread and more a pass of the time. It was, in a way,

exonerating to hear about what it might be like to live somewhere

else in the country.

Mostly, too, he'd begun to look forward to his evenings. His

guard duty less a dread and more a pass of the time. It was, in a way,

exonerating to hear about what it might be like to live somewhere

else in the country.

Elisanna had grown up in Apelles, with her uncle and

brother, and she talked about it with the sweet initiation one might a

bright evening or lovely dress of brass silk. Thin, wispy trees with

white branches and tall grasses that bloomed under a soft summer

sun, not unlike Somset. A beautiful paramount of the summer

season. Much more romantic a childhood than Domerics own, with

its deep mud and thick-rooted sandbox trees.

"And barnacle geese—" Elisanna had said one evening while

describing her childhood in Apelles. Her hand stuck out through the

rusted bars as she used a thin weave of straw to draw divots in the

dirt dusting over the cellar tiles.

"There's no such thing." Domeric had said, and Elisanna

protested.

"It's true. They grow on bushes like a berry. One in every

lake. Swear it."

"Have you ever seen a Barnacle Goose?"

"I have."

"On the tree?"

"Well, not on the tree." Domeric looked at her incredulously,

her lips pushed into a hard line. "Lot's of people say they've seen

em."

"Lots of people say they've seen ghosts."

Though she didn't much see the irony, and Domeric hadn't been sure

whether or not he was being played for a fool.

By the midpoint of the summer swell, Domeric had gotten

quite used to the normalcy of things. Even so much as to consider it

fondly. One, in which they'd served a small tea cake with dinner, he'd

taken one down to the cellars wrapped in a cheesecloth he'd taken

from the kitchens earlier that morning.

"And what's this?" Elisanna had asked as she unfurrowed the

small cloth in her lap, the tea pastry crumpled into the fabrics edge.

"A lemon cake, for your Saint's Day, is it not?" Domeric

watched as she turned the pastry in her hands, eyeing the fine, thin

lines of frosting on the cake's top.

"I hate lemons," she said, her lips pulled to a quaint smile as

she split a bit of the cake off, pressing it under her tongue. "Thank

you."

And as autumn pressed dubious at the edge of the summer

days, Domeric had almost forgotten the temporary nature of the

castle.

Most of the fighting had been taken east, a small rally of

decenters near Lecchour who'd heard about the capture and had taken

up arms at the behest of Elisanna's uncle. And when he'd gone to the

cellar that evening, the cast of Elisanna's forlorn stare had hung

heavily.

"Have you ever killed someone?" Elisanna said gravely, a

sudden repose from Domeric's previous statement, though Domeric

had already forgotten what that had been.

Once. He thought solemnly. A boy his age. The kind that,

under different circumstances, may have been his friend. Instead,

he'd laid face down in the dirt with an arrow through his eye.

Sometimes, he found himself wondering where the boy's Mother

was. Where he was from.

"I've killed many people," Domeric said in a lie. He thought

of knights like Cenric, who certainly had. Thieves and criminals. The

boy that Doemric had killed was neither.

"And did they deserve it?" Elisanna's eyes were wide and

heavy, sunk by frantic thought as they ran over the skin of Domeric's

face. There was no veil of sharp words or jokes, and it was

uncomfortably raw.

No, that is what he wanted to say. Though he couldn't answer

honestly either way. The boy hadn't deserve it. He was simply on the

wrong side of Domeric's arrow.

"It's what had to be done."

The answer didn't seem to quell Elisanna any. Her hands worrying

with the torn skin of her thumbs.

"My uncle took up arms, in the east." She stared intently at

Domeric as her lips formed slow around the words. "They were

going to let me live, you know, the queen was." She tore intently at a

stray piece of skin on her thumbnail. "And now I'm going die in a

city I don't know, for a war I didn't start, by men whose homes I

didn't burn."

It was the quiet truth that Domeric often tried to avoid

thinking about. Because he didn't want to believe it or by some affect

felt guilted by it. It's what has to be done. And there was nothing he

could do, either. Then, for the first time in weeks, he thought of the

woman in the tower, what did she think as she saw the white rocks

below. Domeric wondered.

And he didn't sleep at all that night, taunted by strawberry

hair pinned neatly with a silver arrow.

He'd been called in for his leave later that evening. Ser

Godwin was set to soon leave Somset, and though Domeric tried to

carry on as he normally would, he found his mind often wandered

back to the cellar listlessly.

There’d been a few evenings, in a minor trist of drunken reciprocity,

he'd attempt to make his way down to the cellars, well

unsuccessfully. And Domeric hadn't know either of the men Ser

Godwin kept by his sides well enough to simply ask to be let

through. The severity of the situation slowly weighing on him as the

week poured by.

"Where's Ser Godwin?" he’s said to Bello, one afternoon at

the training yard. Domeric hadn't seen him the evening prior, or that

morning for breakfast, and he'd been worrying the thought endlessly.

"Godwin?" Bello said, face twisted in the flat confusion he

normally held. "Rode off this morning with the captive lady and

whatnot, Certes I think.”

The Queen's city, and he'd only needed a minute to reason

why.

Bello had hung open his mouth to ask something, but

Domeric had already made his way long down the path to the stables.

Chest burning with a sudden sense of fear.

"Where are you going?" He heard Bello call out after him,

taking off in a jog and a wild wave.

"To the city."

“Ydolastre?” Bello asked.

“Certes.”

"You out your mind?" Bello called. "I always knew you were

a basket case, Dom, I mean really, but Certes?" He said. "Well what

the hell is in Certes?"

"You said they're going to Certes." Bello had followed him

all the way to the stables. "They're going to behead the Seymour

girl."

"You're talking treason you know." Bello said, as Domeric

threw a saddle over Favel’s back, the one Toke always left for

Llewellyn’s horse Morel. Bello stepped right in front of Favel, who

was uncharacteristically calm, despite the racket and commotion.

"What of it?"

"I mean think about it Dom, you even have a plan out the

gate?"

"The back gate."

"It's plain as day out."

"If they ask, I'll tell them, Ser Dane sent me off, to catch up

with Godwin."

"By gods Dom." Bello said, mouth hung in disbelief. "You

really are an idiot."

Domeric heeled Favel's reins, kicking him into gear the way

of the gate.

"A foolish, dead, idiot." Bello shouted, and for a moment,

Domeric thought there were worse thing he could be.

The sun had risen to its high point along the skyline by the

time Domeric had reached the caravan. A several hour long ride

along the footpath, and Domeric had been driving them at a

punishing pace, Favel, uniquely grave and deathly quiet as his

hooves hit against the shallow grass fields and through a deep grove

of birch trees beyond the hem of the castle walls, with ground roots

that roamed upward from the dirt like slim fingers.

The sun had risen to its high point along the skyline by the

time Domeric had reached the caravan. A several hour long ride

along the footpath, and Domeric had been driving them at a

punishing pace, Favel, uniquely grave and deathly quiet as his

hooves hit against the shallow grass fields and through a deep grove

of birch trees beyond the hem of the castle walls, with ground roots

that roamed upward from the dirt like slim fingers.

He was pretty certain none of the men in the caravan had

seen him, their faces forward, faced north, and the open green fields

that wrapped the hillside obscuring them to a small weave in the

distance. Their figures still and stopped as they spoke in carried

voices.

Domeric pulled an arrow from his back and notched it in his

bow, feet pressed tightly to his saddle as he tried to hold himself

upright.

There were two men along with Godwin in the caravan, and

Domeric would never win a fair fight, unlikely against one, and

certainly not three, he thought, as he loosed one of the arrows off

towards the deep, flushed, sky, the steel whipping past and loaning

itself into the dirt aimlessly.

The sudden shot caused a fuss up ahead as Favel inched

closer on the gap, wide leaps covering distance faster than the men

could mount their horses. Their broad hands pointing to Domerics'

spot on the horizon.

He notched another arrow, this time trying to steady the

pallid shake in his hands as they gripped around his bow. He aimed

for one of the men who had been stopped on foot as he clamored to

the back of his horse, a quick relay in Domeric's direction. And when

he loosed the arrow, he watched the shot bury itself in the man's chest, soft in the spot between his breastplate where his shoulder met

his body.

Domeric watched colourlessly as the hit knocked the man

backward to the ground, landing in the dirt with a sickly sound, his

body bent against the soft grass. He'd almost wished the man might

get back up, in some horrible sense of alleviation, before he realized

how terrible that would be. And that he'd made the choice before he'd

ever shot the arrow.

And before he could give the dead man further thought, he

loosed a second arrow, this time on the other man who'd pulled a

long bow from his back, the first shot wedging itself in the man's

draw arm, the second in his throat. The shouts of confusion rose as

he closed the distance.

"Domeric?" He heard Elisanna ask, her voice ringing

soundly like the echo of a canyon throught the rolling hills. "What

the hell are you doing here? Oh damn you Domeric!" She yelled, her

voice pitched high in a shrill of fear, though her eyes shone wide

under the deep noon sky.

"Quite!" He heard Godwin shout as he dismounted his black

war horse. Voice stone like a tempered cliff face. "What's this about?

You damn fool."

And for a moment, Domeric hadn't known what he'd wanted

to say.

"You can't go to Certes." Domeric said, finally. It was a

terrible plea he knew. Fallen on the moment in deathly silence.

"You killed two of my knights,” Godwin said, sword still

sheathed and eyes hung tightly, “to tell me I can't go to bloody

Certes?" And Domeric could only nod to where Elisanna sat on the

back of the black horse, A look of terrible understanding crass on

Godwin’s face. "Is that how you want it to be?" Godwin asked, and

Domeric felt his first tighten around the hilt of his sword.

"You'll never see us again, swear it." Domeric said. "We'll go

across the sea, to Soveryen." But Ser Godwin just shook his head.

"Two men are dead, boy." He pulled off one of his white

gloves, pressing it under his arm as he pulled for the other. "You

don't just get to walk away from this." He could see the etched

hardness ridgid in Ser Godwin's expression as he stood, cold and

weathered but not disturbed or even filled with pity and grief from

the deaths. But rather the weariness that comes simply with time.

"Put down your arms, and I won't kill you dead."

Instead, Domeric drew his sword, point raised to Ser

Godwin's chest.

"Are you an idiot?" Ser Godwin shouted this time. "I said put

down your damn arms.” And Domeric shook his head flatly. “You

know how to use that well, that weapon of yours?" His voice was

hoarse like gravel. And Domeric raised his sword an inch higher, the

weight burning through the tips of his fingers as Ser Godwin closed

his eyes to the intrusive sun. “You're a child with a sword.”

"A knight." Domeric said, and Ser Godwin laughed.

"The idiot knight, maybe." And before Ser Godwin could

speak further Domeric swung the heavy steel flat towards him, the

hit narrowly parried as Godwin stepped back, unalarmed.

“You're not stupid. Throw the damn thing down.” Ser

Godwin barked again, and the time, Domeric hit the hilt of his blade

in the Templar knights chest, knocking him flat to the floor as he saw

Elisanna lurch from her spot on horseback, hands bound at the wrist.

He felt Godwin's grip on his forearm as he fell, pulling him

down to the dirt roughly and landing a clean punch against Domeric's

face, he could feel blood begin to drip from his nose, but his instincts

had kicked in, the sudden realization that he was outmatched

weighing on him.

He hit Ser Godwin again, harder, causing the man to wheeze.

Though the punch did little to ease the hand pressed on Domeric’s throat, like a dog that had been run loose on the pasture. The shallow

sky waning in the distance, A thick clot of clouds cut by the bleached

sum hanging sick overhead, full of sweet, soft rains set to break

likely into a waring shower week, or even months down the line. He

hit Godwin again, and twice more, the sharp end of his sword slicing

thick against Ser Godwin's side in a terrible noise.

"To all the hells." Is all Godwin said, a spray of blood and

cashmere rippled against Domeric's face as the sword sunk deeper in,

the arm on his throat gone as it grabbed to pull the sword from his

side. And before he'd been struck by the pain, the warm puddle

blossoming down the length of his chest told him something was

terribly wrong.

He heard a soft sound from the distance then, like a wail, the

sky dimmer, the view of a pinhole. And then the heavy weight of

Godwin slumped off him, and Elissaina stood dazed above him. Her

hands were ripe and red as they dragged him from the dreamless

ground. His back flat against a horse. Though he wasn't sure whose.

"Damn you." He heard her say again, and though the sky was

clear, he felt the fall of rain as it wet the edge of his cheek. His heart

pounding horribly and the sky racing above in a fine blur. Faintly, he

could hear the sound of Elisanna's voice hung over him, but no

words came out. A pair of egrets stamped to the clouds overhead, all

long white wings as they flew above the summer hills. And awfully

enough, Domeric thought, they were loud as all terror, like soft,

terrible ghosts.

In the years before he turned seventeen, Domeric had grown

up in the harder half of the country. Red marshes and thick groves of

dirt and dead men that had wandered off an eye too far and foot too

deep, like haunted marks that marred the flat plains of swamp, buried

only a stone’s throw from the foot path unbeknownst to the

passerby’s until their bodies came up with the summer rains.

In the years before he turned seventeen, Domeric had grown

up in the harder half of the country. Red marshes and thick groves of

dirt and dead men that had wandered off an eye too far and foot too

deep, like haunted marks that marred the flat plains of swamp, buried

only a stone’s throw from the foot path unbeknownst to the

passerby’s until their bodies came up with the summer rains.

According to Bello, she was a well built brunette who

frequented the local alehouse, though Domeric had his suspects that

she didn’t spend her evenings waiting there for folks like Bello to

sweep her off her feet in romantic tizzy.

According to Bello, she was a well built brunette who

frequented the local alehouse, though Domeric had his suspects that

she didn’t spend her evenings waiting there for folks like Bello to

sweep her off her feet in romantic tizzy.

For the most part, in the week to follow, Domeric had spent

most of his time at the small wooden desk shoved in the far corner of

his room. Several shelves worth of books piled around in small

puddles as he made work of reading through the leafed pages.

He'd found, quite unfortunately, there was very little to do outside a

litany of chores and base responsibilities, besides perhaps drink and

sew havoc on the small town of Ydolastre that was a half-hour ride

away, which hadn't been allowed, but many of the boys did anyway.

For the most part, in the week to follow, Domeric had spent

most of his time at the small wooden desk shoved in the far corner of

his room. Several shelves worth of books piled around in small

puddles as he made work of reading through the leafed pages.

He'd found, quite unfortunately, there was very little to do outside a

litany of chores and base responsibilities, besides perhaps drink and

sew havoc on the small town of Ydolastre that was a half-hour ride

away, which hadn't been allowed, but many of the boys did anyway.

That evening, he dreamed he drowned in a sea of grass, and he'd

awoken to the cold light of the morning sun as it barely ran thin over

the crossed glass of his chamber's window.

That evening, he dreamed he drowned in a sea of grass, and he'd

awoken to the cold light of the morning sun as it barely ran thin over

the crossed glass of his chamber's window.